After Italy’s defeat at Caporetto by the German and Austro-Hungarian armies in October 1917, over three hundred thousand Italian soldiers were taken prisoner. The Italian government and military forces, embarrassed by how easily the weaknesses of their forces near the River Piave had been exposed, were quick to find scapegoats. The POWs, stamped as deserters, were made to take the blame for their country’s defeat by the Central Powers. Scattered in lager across Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italian authorities made a point of not sending food parcels to their captured compatriots. Subsisting on desperately meagre rations, the mortality rate of Italian soldiers in captivity was even higher than it was on the frontlines. One in six prisoners died, often from hunger-related diseases.

After Italy’s defeat at Caporetto by the German and Austro-Hungarian armies in October 1917, over three hundred thousand Italian soldiers were taken prisoner. The Italian government and military forces, embarrassed by how easily the weaknesses of their forces near the River Piave had been exposed, were quick to find scapegoats. The POWs, stamped as deserters, were made to take the blame for their country’s defeat by the Central Powers. Scattered in lager across Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italian authorities made a point of not sending food parcels to their captured compatriots. Subsisting on desperately meagre rations, the mortality rate of Italian soldiers in captivity was even higher than it was on the frontlines. One in six prisoners died, often from hunger-related diseases.

The captured soldiers’ inevitable response to the enforced inactivity and starvation was to talk about food. “Little by little, hunger became a kind of delirium: we talked of nothing but eating, and waited only for the moment when the miserable bowl of slops was distributed,” wrote the POW Giovanni Procacci in his memoirs. At some point, the Genoese Second Lieutenant Giuseppe Chioni, interned in the officers-only camp of Celle, near Hannover, felt compelled to alleviate the hunger and physical hardship he and his fellow prisoners were enduring by compiling a recipe compendium called Arte culinaria (‘Culinary Art’). In his preface, written on the lined paper of a flip-pad, Chioni writes of “the metamorphosis that has turned us from warriors to cooks”:

Long periods of fasting force us to stay curled up so that the cramps of hunger feel less strong, and to remain motionless for whole days so as to waste less energy. Bear this in mind, and it will seem natural that, in our need for the home hearth, each of us has remembered the exquisite meals and appetising sauces prepared by the delicate and caring hands of a far distant mother or wife.

That unassuming flip-pad, now stored in L’Archivio storico della Provincia di Genova, was probably the most geographically representative Italian cookbook that had ever been written. As we saw in the first edition of My Kitchen Shelf, Pellegrino Artusi’s culinary map of the young nation in 1891 was distorted in favour of Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany, the regions the eccentric bachelor from Forlimpopoli knew best. Many other places were overlooked or given tokenistic treatment in Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well. Chioni, however, transcribed the recipes of comrades hailing from regions all along the peninsula and its islands in Arte culinaria.

An enormous amount of thought went into Chioni’s prison-penned manuscript. Containing over 400 recipes, it is divided into eleven sections: antipasti, sauces, soups and pastas, pizzas, fish, meat and game, omelettes and eggs, polenta, bread, vegetables, and beans, sweets and jams. Each section commences with a title page featuring an illustration of the foods in question. Poignantly inexpert drawings of a fish, a squid and a skillet for frying accompany the Fish section, for instance. The recipes, ranging from Piedmont’s bagna cauda to Sicily’s cannoli, are recalled with care and longing. Only a handful, such as a Zuppa stravagante (“Extravagant Soup”) containing lard, pancetta and ham, seem to be the hallucinatory stuff of dreams of starving men.

Chioni’s recreation of an Italian Land of Plenty also provides us with clues to the evolution of many traditional Italian dishes. Surprisingly enough, the sauces ragu alla bolognese and pesto alla genovese, often subject to futile attempts at codification these days, appear to have been prepared in way that would have today’s culinary purists raise their eyebrows. The ingredients list for Bologna’s most famous export, for example, includes veal, mortadella and ham which are to be fried in butter. Absolutely no mention of pancetta, carrot, celery, onion, tomato, white wine, milk, broth, olive oil – all ingredients held to be ‘authentic’ by the Accademia Italiana della Cucina – is made. The pasta it is be served with, held to be tagliatelle (never spaghetti!) these days, is not specified either. As for pesto alla genovese, here is how Giuseppe Chioni, a native of the port city, would have prepared it:

Pesto alla Genovese. Basil, garlic, parsley, a little onion, marjoram, spices, Sardinian pecorino cheese. Grind everything in the mortar and reduce it to a pulp. To use, add raw oil.

The manuscript is also remarkable for its inclusivity. Artusi, in contrast, made no attempt to disguise any biases or value judgements he held about certain preparations in Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Cooking Well, especially those he held to be unrefined or not belonging to ‘the comfortable classes’. Curiously enough, one of those ‘unrefined’ dishes was pollo in porchetta, a dish featuring an ingredient – a whole spit-roasted chicken stuffed with ham – that the majority of Italy’s mostly peasant and sharecropping population would have probably only dreamed about eating at the time! The officers, on the other hand, included the rich, meat-laden dishes that only the well-off would have been able to afford as well as humbler fare such as polenta, legume and vegetable-based preparations. Any trace of snobbery regarding food from the home hearth had vanished with the officers’ hunger.

You can’t help but imagine the officers’ conversations either. For Chioni and his fellow prisoners, this was probably the first time they had come into contact with the many different dialects and accents from their young nation. It is amusing, for instance, to see how Chioni has recorded the recipe for spaghetti alla amatriciana, a Roman primo made with tomatoes and guanciale (‘jowl bacon’). The ingredients and method are all correct but he’s transcribed the dish as spaghetti alla madrigiana. To Chioni’s northern Italian ears, that was probably how the dish’s name sounded when pronounced by one of his presumably Roman comrades. Chioni, however, made a faithful record of the country’s ‘anchovy’ divide. Southern recipes which include these fish call for alici while the word acciughe features in northern and central Italian anchovy-based preparations.

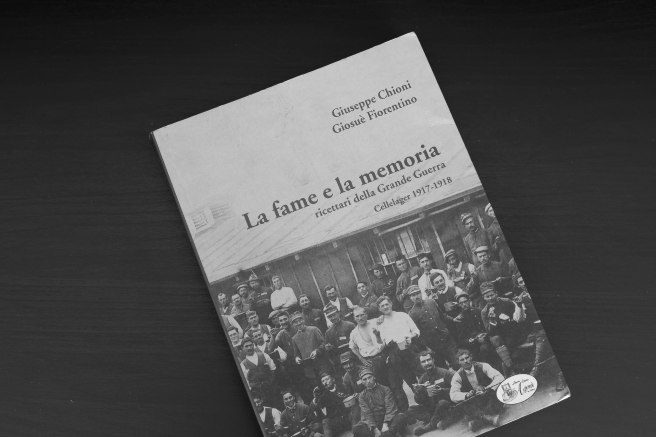

Writing about Italy’s gastronomy sustained Chioni until the armistice of November 1918. He then returned to Genoa, got married and returned to his previous occupation as a deputy stationmaster. In 1959, he died at the age of 64. His handwritten opus was kept secret for two generations, until its contents came to the attention of his granddaughter, Roberta Chioni, the Archivio storico della Provincia di Genova and the historians Fabio Caffarena and John Dickie. In 2008, alongside another World War I recipe book penned by the Sicilian POW Giosuè Fiorentino, Arte culinaria was finally published in the Italian-language volume La fame e la memoria: ricettari della Grande Guerra. It is my hope that Chioni’s recipe compendium, one of the most remarkable and moving documents in Italian culinary history, will one day be available in English and other languages too.

Sources and suggestions for further reading:

Pellegrino Artusi, Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well

Giuseppe Chioni e Giosuè Fiorentino, La fame e la memoria: ricettari della Grande Guerra

John Dickie, Delizia! The Epic History of Italians and Their Food

Massimo Montanari, Italian Identity in the Kitchen, or Food and the Nation

Gillian Riley, The Oxford Companion to Italian Food

Nicholas Walton, Genoa, ‘La Superba’: The Rise and Fall of a Merchant Pirate Superpower

Is this a recent publication? I went to Amazon.it and looked for La Fame e la Memoria and could not find a listing. I’ll keep trying but would appreciate any further information you might have–publisher, pub date, etc. Grazie mille!

LikeLike

Hi Nancy, Thanks for dropping by! The book was published in 2008 by the publishing house Agorà Libreria Editrice. Amazon doesn’t appear to have it in stock right now. I ordered my copy from here: http://www.libreriaagora.com/web/editore/catalogo.html?page=shop.product_details&flypage=flypage_libreriaagora.tpl&product_id=28&category_id=3

Another ordering option is at this link: http://www.ibs.it/code/9788888422480/chioni-giuseppe/fame-memoria-ricettari.html

Hope this is helpful 🙂

LikeLike

Ahime! When I finally found it, it said “non disponibile.” Any further suggestions?

Nancy Jenkins

LikeLike

Hi Nancy,

I’m sorry to hear that the book wasn’t ‘disponibile’. Here are a couple more ordering possibilities

Here are a couple of other sites you could order it from:

http://www.edizionidbs.it/shop/grande-guerra/la-fame-e-la-memoria-ricettari-della-grande-guerra-cellelagher-1917-1918/

http://www.libreriauniversitaria.it/fame-memoria-ricettari-grande-guerra/libro/9788888422480

Fingers crossed it’s available at one of these sites…

LikeLike